Author

Elizabeth (Izzy) Montgomery, MPA

Policy Analyst

Contact

ACHI Communications

501-526-2244

jlyon@achi.net

(Original post published July 24, 2019)

As Arkansas and other states battle an ongoing opioid crisis, concerns about infectious diseases resulting from injection drug use warrant increased attention from policymakers. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), approximately 775,000 Americans reported injecting a drug based on estimates from a 2014 modeling study. Injection drug use has increased the number of viral hepatitis infections, according to a recent Arkansas Democrat-Gazette story on a rise in hepatitis C cases in Arkansas. Injection drug use has also stymied human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevention efforts and has led to an increase in drug overdose deaths. One strategy for reducing infectious diseases and overdose rates among persons who inject drugs is adopting syringe service programs (SSPs), also known as needle exchange programs.

SSPs are community-based prevention programs that provide a number of services to persons who inject drugs. Typical services include:

- access to new, sterile needles and syringes

- safe disposal site for used products

- vaccinations

- testing

- referral to care and treatment

There is evidence demonstrating that SSPs can help people stop using drugs and reduce the spread of infections without increasing criminal activity. As the CDC notes, studies have established that individuals who are new users of SSPs are five times more likely to enter drug treatment programs than those who do not use SSPs. Evidence has also shown that SSPs do not increase illegal drug use, are cost-effective, and reduce drug use and overdoses. Additionally, SSPs can increase public safety by reducing needle-stick injuries for first responders and reduce the overall presence of needles within a community.

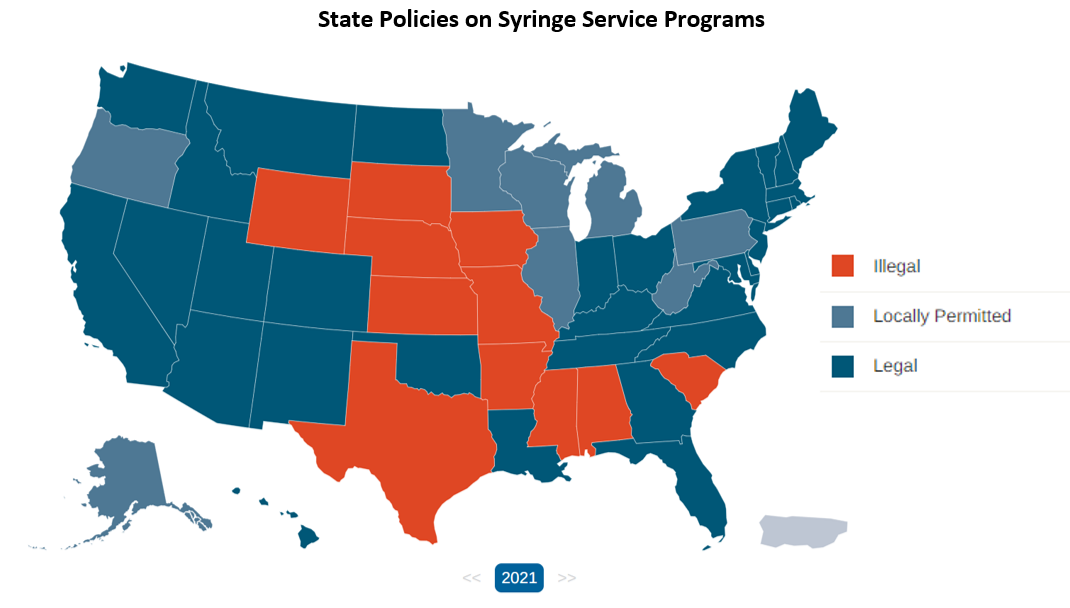

SSPs are just one component of a comprehensive prevention program. The decision to establish an SSP is made at the state or local level. According to data tracked by the HIV Prevention Justice Alliance, 31 states and the District of Columbia have authorized SSPs statewide in legislation. In another eight states, local health departments have interpreted state laws to allow for SSP services or have determined that there are no laws prohibiting SSPs. In another 11 states including Arkansas, SSPs are still considered illegal.

The ACHI Health Policy Board is supportive of SSPs as a strategy to decrease the incidence and prevalence of HIV and other infectious diseases in Arkansas, as outlined in the Board’s position statements.