Arkansas is the only state in the U.S. without an implied warranty of habitability — a basic protection that holds landlords accountable for maintaining livable housing.[1] Although there have been legislative efforts in recent years to ensure safe and sanitary living conditions for tenants of rental properties in Arkansas, those efforts have been limited. The state adopted minimum residential quality standards in 2021, but tenants still lack meaningful legal recourse when landlords fail to meet those standards.[2] The substandard housing conditions that occur in the absence of enforceable habitability standards affect individual and community health. This explainer provides information on the impact of housing on health, the housing status of Arkansans, the effects on substandard or unstable housing on maternal and infant health, and policies designed to improve housing, including implied warranty of habitability

Housing Conditions

Aging infrastructure, economic disparities, and rural-urban divides all contribute to the ongoing challenges of housing conditions in Arkansas. Individuals and families who rent property in the state may face challenges securing safe and healthy housing. Common problems include plumbing and electrical deficiencies, mold and mildew, pest infestations, poor insulation, and other environmental hazards.[3] According to a 2017 health impact assessment by the Arkansas Community Institute and the Central Arkansas Re-Entry Coalition, tenants with limited financial resources are especially at risk, often remaining in hazardous conditions due to fear of retaliation, limited housing alternatives, or lack of knowledge about their rights. These challenges are particularly pronounced for low-income renters, older adults, children, and pregnant women.

Young people are especially vulnerable. On a single night in January 2024, Arkansas had the highest rate of unsheltered, unaccompanied youth in the nation at 66%, followed by California and Oregon, both at 60%.[4] According to Arkansas Department of Education data, 295 children in the state were unsheltered during the 2024-25 school year.[5] Research shows that those who grow up with unstable housing are more likely to be unhoused in the future.[6]

Poor housing conditions can also disrupt family stability. Families experiencing eviction, unsafe living conditions, or frequent moves are more likely to encounter intervention by child protection systems.[7] Housing challenges can increase parental stress and expose children to unsafe conditions. When children are removed from their homes, lack of stable housing can also delay reunification, as parents are often required to secure safe, adequate housing before regaining custody. Ensuring that families in Arkansas can remain together in safe, stable housing is not just a housing issue; it is important for family preservation and long-term child well-being.

Why Housing Matters for Health

Housing is a key driver of health, shaping exposure to risks and access to resources across every stage of life.[8] In the United States, people who experience homelessness die nearly 30 years earlier than the average American.[9] A person’s environment influences access to education, employment, public safety, proper nutrition, medical care, and transportation.[10] In Arkansas, deficits in these areas are linked with increased morbidity and reduced life expectancy, especially in certain parts of the state.[11] For example, a more than 10-year difference in average life expectancy exists between Phillips County (68 years) and Benton County (78.8 years).[12] Polk County, which is ranked as one of the worst counties in the state for severe housing problems, has a life expectancy of 72.6 years, two years below the average life expectancy in Arkansas and almost five years below the national average.[13]

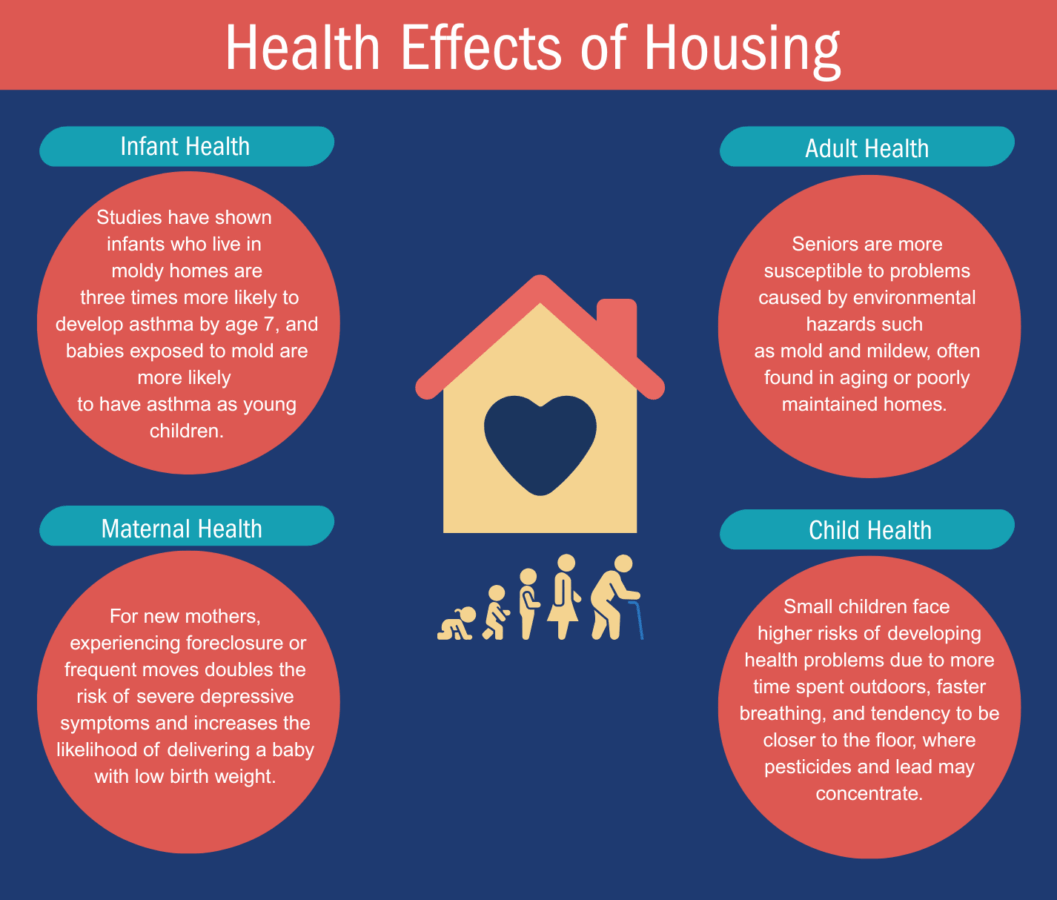

Poor housing conditions are also associated with health conditions such as asthma, heart disease, cancer, and respiratory illness.[14] For children, unsafe housing can affect physical and mental health and interfere with academic performance. Research shows that even intermittent periods of housing instability during childhood can elevate mental health risks later in life, and instability during the first three years of life has the strongest correlation with later poor health outcomes.[15] Unsafe housing can also contribute to chronic stress in adults and families, which contributes to a wide range of poor physical and mental health outcomes. These challenges are often intensified for those with fewer resources.

Why Housing is Critical for Expecting Families

Arkansas consistently ranks among the worst states in the nation for maternal and infant health outcomes.[16] The state’s rates of both maternal mortality[17] and infant mortality[18] typically are among the nation’s highest.

Stable, safe housing is important for healthy pregnancies and healthy babies. Housing insecurity before or during pregnancy has been linked to higher levels of maternal stress and depressive symptoms, which in turn contribute to adverse birth outcomes.[19]

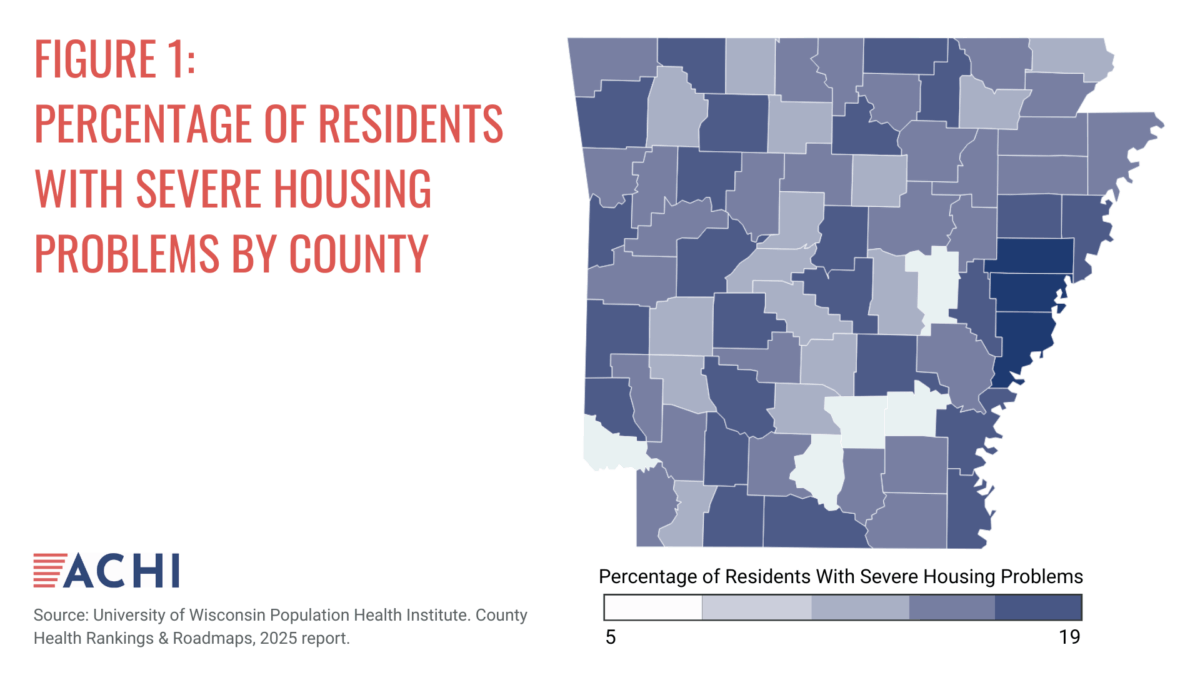

A look at a single Arkansas county may help to illustrate the connection between housing and health. In Lee County, which is among the Arkansas counties with the highest rates of severe housing problems (see Figure 1), 19% of residents have at least one of four housing problems: overcrowding, high housing costs, lack of kitchen facilities, or lack of plumbing facilities.[20] The county also has a high rate, 14%, of babies born with low birth weight.[21] This striking overlap between housing deficiencies and poor infant outcomes highlights the importance of housing as a public health intervention point. Homelessness is both a cause and effect of health disparities in the state, and this bi-directional relationship is especially burdensome among vulnerable populations including mothers, infants, children, and seniors.[22]

FIGURE 2: HEALTH EFFECTS OF HOUSING[23],[24]

Impacts on the Healthcare System

Unstable or substandard housing conditions also strain the healthcare system. Individuals living in inadequate housing are more likely to require emergency care or hospitalization for conditions that could have been prevented with safe, stable housing, such as asthma attacks, injuries, and chronic disease complications.[23] A 2020 study found that poor housing quality is associated with increased odds of both medical usage and hospitalization, even after controlling for income and insurance status.[25]

Providing access to stable housing can improve health and reduce healthcare costs. A 2015 study compared tenants residing in low-income public housing that had been redeveloped using sustainable, “green” construction practices with tenants whose housing had been renovated using traditional, “non-green” methods.[26] The researchers found that new, environmentally friendly construction practices increase the self-reported general, physical, and mental health of tenants.

Solutions That Support Healthy Housing

Housing-related health issues can be decreased through multiple policy pathways at both the federal and state levels.

Medicaid Support for housing-related services

States can address housing-related health issues through various Medicaid mechanisms, including waivers, state plan amendments, and managed care flexibilities.[27] A 2018 survey conducted by the National Center for Healthy Housing found that 13 states provided Medicaid reimbursement for home-based asthma services, three states planned to begin providing reimbursement for these services within a year, and 19 states were exploring this option.[28]

Arkansas has used a Section 1115 Medicaid demonstration waiver to implement a program called Life360 HOMEs that seeks to reduce homelessness by identifying young adults at high risk for long-term poverty and helping them build their emotional, physical, and social skills.[29] However, there remain significant opportunities to expand and align Medicaid policy to support housing-related interventions that improve health outcomes and reduce costs. For example, North Carolina became the first state to use community-based organizations to address the housing needs of Medicaid enrollees when it launched the Healthy Opportunities Pilots Program. The purpose of the program was to test and evaluate the impact of providing evidence-based, non-medical interventions related to the housing and other social needs of Medicaid enrollees.[25] As of July 2025, the program is no longer being funded by the North Carolina General Assembly, but it could still serve as an example for Arkansas. Key components of the program included:

- Identifying variations in housing resources and needs.

- Defining and pricing housing services in Medicaid.

- Engaging diverse stakeholders across sectors.

- Developing sustainable financial models.

Home-Based Interventions

Home-based interventions are a strategy for improving health outcomes linked to housing conditions, particularly for children and families living in older or low-quality housing. These evidence-based approaches focus on reducing harmful exposures inside the home to improve health and reduce preventable medical costs. Examples include replacing windows to decrease lead dust throughout the household and installing mechanical ventilation to decrease indoor pollutants.

Statistics suggest Arkansas would benefit from expanded home-based interventions. In 2021, 112 children in Arkansas were reported to have elevated levels of lead in their blood.[30] A study conducted in Chicago and funded by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development showed that replacing windows led to a significant decrease in lead dust throughout the household.[31] On average, lead dust declined by 54%, and the percentage of children experiencing earaches, respiratory allergies, headaches, and uncomfortable indoor temperatures declined. There was also a predicted economic benefit of $2.5 million from gains in lifetime earnings due to avoided loss of IQ.

Implementation of mechanical ventilation has also proved to be beneficial. A longitudinal study conducted in 152 affordable homes across multifamily properties in Chicago and New York City found that mechanical ventilation was effective in reducing levels of five common indoor pollutants and improving the respiratory and cardiovascular health of residents.[32]

Housing improvements that address asthma triggers have proven cost-effective. A review by the Community Preventive Services Task Force found that home-based, multi-trigger, multi-component interventions for children and teens with asthma improved quality of life, reduced symptoms, and lowered healthcare use.[33] Economic evaluations showed a return of $5.30 to $14 for every $1 invested. In Massachusetts, a Medicaid program offering home visits and environmental remediation for children with uncontrolled asthma resulted in fewer attacks, urgent care visits, and missed school days, along with a positive return on investment.[34]

Leveraging hospital community benefit spending

Home-based interventions have demonstrated promising outcomes on a small scale, but broader and more sustainable impacts can be achieved by leveraging nonprofit hospitals’ community benefit expenditures to support housing and health initiatives. Under federal tax law, nonprofit hospitals are required to invest in activities that address community needs.[35] While many assume that most of that investment goes to community health improvement activities and charity care, a national analysis found that in 2015, just 25% of total community benefit spending supported charity care and just 5% supported community health improvement, while the remaining 75% went toward Medicaid shortfalls, teaching, research, and subsidized services.[36]

While large urban teaching hospitals often have the resources needed to support community health benefit programs, smaller rural hospitals typically have more limited resources. Given that approximately 44% of Arkansans live in rural areas, greater funding and support for hospital programs that target issues in the community such as poor or unstable housing, even if these investments are smaller than those in urban settings, could help address housing-related health challenges in the state.[37]

Hospitals can boost their community health benefit spending by, for example, screening patients for housing insecurity and connecting them to community organizations that can help. Some states have mandatory thresholds for community health benefit spending. Utah and Illinois require that nonprofit hospitals’ spending on community health improvement match or exceed, respectively, their property tax liability. Oregon has a community health benefit spending threshold that is revisited every two years.[38] Policymakers could consider adopting a similar threshold in Arkansas as one way to address housing-related health issues.

Legal Landscape Related to Tenant Protections

The federal government sets minimum property maintenance standards for housing receiving federal assistance, requires landlords to disclose lead hazards, and ensures fair housing without discrimination.[39] However, there is no comprehensive national housing health code, and many health-related protections are left to state and local jurisdictions.

As noted above, Arkansans are particularly vulnerable because Arkansas is the only state without a statewide basic tenant rights law — an implied warranty of habitability — requiring landlords to maintain a habitable rental property.1 This absence leaves many tenants with limited recourse when faced with serious housing deficiencies such as structural hazards, mold, faulty plumbing or wiring, or heating failures.

Arkansas Act 1052 of 2021[40] marked progress by establishing minimum residential quality standards for rental agreements — such as access to hot and cold running water, functioning electrical and plumbing systems, and functional roofing — but the law does not provide tenants with an avenue to enforce those standards in court.[41] If a landlord fails to meet these obligations, the tenant’s only option under the law is to terminate the lease without penalty.

Some cities, including Little Rock, have taken additional steps. Arkansas’s capital city has codified key tenant protections for multi-family housing, including the provision of hot and cold water, plumbing, heating and air conditioning, and a functioning roof, in addition to general maintenance.[42] However, such protections are limited to specific localities, and many rural areas and small towns in Arkansas lack housing codes altogether.

This lack of statewide protections is especially concerning given that 40% of Arkansas homes were built prior to 1978, increasing the risk of lead exposure, poor insulation, and outdated infrastructure.[43] Without statewide enforceable habitability standards, tenants in substandard housing — particularly those with fewer financial resources — often have no formal path to demand safe, healthy living conditions. Despite multiple legislative attempts over the past decade, Arkansas has yet to adopt comprehensive renter protections to ensure habitability.

Conclusion

Arkansas is an outlier in the U.S. in regard to basic tenant protections from poor living conditions, which can lead to poor health outcomes. Establishing regulatory protections like those in other states could improve clinical outcomes, reduce medical costs, and increase tenants’ overall health and well-being. Potential savings resulting from fewer days of missed work and school and more appropriate medical utilization could offset the costs of improving housing conditions in Arkansas.

References

[1] Rogers, M. (2022, April 1). Landlord-tenant rights: Arkansas’ failure to adopt habitability requirements for Tenants. University of Arkansas at Little Rock. https://ualr.edu/socialchange/2022/04/01/landlord-tenant-rights-arkansas-failure-to-adopt-habitability-requirements-for-tenants/

[2] Arkansas Act 1052 of 2021. https://arkleg.state.ar.us/Home/FTPDocument?path=/ACTS/2021R/Public/ACT1052.pdf

[3] Arkansas Community Institute & Central Arkansas Re-Entry Coalition. (2017, November). Assessing the health and equity impacts of Arkansas’s landlord-tenant laws. https://www.pew.org/-/media/assets/2018/09/warranty-of-habitability-in-arkansas-hia.pdf

[4] de Sousa, T., & Henry, M. (2024, December). The 2024 annual homelessness assessment report to Congress. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/2024-AHAR-Part-1.pdf

[5] Arkansas Department of Education. Homeless by type by county. ADE Data Center. Accessed July 22, 2025. https://adedata.arkansas.gov/statewide/reportlist/Counties/HomelessByType.aspx

[6] Parpouchi, M., Moniruzzaman, A. & Somers, J. M. (2021). The association between experiencing homelessness in childhood or youth and adult housing stability in Housing First. BMC Psychiatry, 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03142-0

[7] National Conference of State Legislatures. (2025, January 20). Strengthening families through housing stability. https://www.ncsl.org/human-services/strengthening-families-through-housing-stability

[8] Ahmad, N., & Mark, J. (2019, July 22). Home is where our health is. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. https://www.rwjf.org/en/insights/blog/2019/07/home-is-where-our-health-is.html

[9] United States Interagency Council on Homelessness. Homelessness data & trends. Accessed July 22, 2025. https://usich.gov/guidance-reports-data/data-trends

[10] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2021). Community health and economic prosperity: Engaging businesses as stewards and stakeholders—A report of the surgeon general. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/chep-sgr-full-report.pdf

[11] United Health Foundation. Severe housing problems in Arkansas. America’s Health Rankings. Accessed July 22, 2025. https://www.americashealthrankings.org/explore/measures/severe_housing_problems/AR

[12] Arkansas Department of Health. (2022). Red county: County life expectancy profile. https://healthy.arkansas.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022_Red_County_Report.pdf

[13] University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, County Health Rankings & Roadmaps. Polk, AR. Accessed July 22, 2025. https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/health-data/arkansas/polk?year=2025

[14] Redwood, Y., Schulz, A. J., Israel, B. A., Yoshihama, M, Wang, C. C., & Kreuter, M. (2010). Social, economic, and political processes that create built environment inequities: Perspectives from urban African Americans in Atlanta. Family & Community Health, 33(1), 53‒67. DOI:10.1097/FCH.0b013e3181c4e2d4

[15] Pierce, K. A., Mendelsohn, A., Smith, B., Johnson, S. B., & Duh-Leong, C. Trajectories of housing insecurity from infancy to adolescence and adolescent health [Video]. Accessed July 22, 2025. https://video.publications.aap.org/pedsvideoabstracts/detail/videos/all-video-abstracts/video/6353448118112

[16] Lyon, J. (2024, July 22). Arkansas ranked near bottom of states in maternal health scorecard. Arkansas Center for Health Improvement. https://achi.net/newsroom/arkansas-ranked-near-bottom-of-states-in-maternal-health-scorecard/

[17] KFF. Maternal deaths and mortality rates per 100,000 live births. Accessed July 29, 2025. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/state-indicator/maternal-deaths-and-mortality-rates-per-100000-live-births/?currentTimeframe=0&selectedDistributions=maternal-mortality-rate-per-100000-live-births&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Maternal%20Mortality%20Rate%20per%20100,000%20Live%20Births%22,%22sort%22:%22desc%22%7D

[18] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Infant mortality rates by state. Accessed July 22, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/sosmap/infant_mortality_rates/infant_mortality.htm

[19] Leifheit, K. M., Schwartz, G. L., Pollack, C. E., Edin, K. J., Black, M. M., Jennings, J. M., & Althoff, K. N. (2020). Severe housing insecurity during pregnancy: Association with adverse birth and infant outcomes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 8659. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228659

[20] University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, County Health Rankings & Roadmaps. Severe housing problems. Accessed July 29, 2025. https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/health-data/community-conditions/physical-environment/housing-and-transportation/severe-housing-problems?year=2025&state=05

[21] University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, County Health Rankings & Roadmaps. Lee, AR. Accessed July 29, 2025. https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/health-data/arkansas/lee?year=2025

[22] Montgomery, B. E. E., Crone, C., Goodwin, B., Hokans, R., Williams, A., Stacker, J., Borné, R., Pro, G., & Martel, I. (2024). Home together: A multi-level community-based health promotion program supporting families experiencing homelessness. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 35(3), 880‒902. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2024.a934304

[23] Iossifova, Y. Y., Reponen, T., Ryan, P. H., Levin, L., Bernstein, D. I., Lockey, J. E., Hershey, G. K. K., Villareal, M., & LeMasters, G. (2009). Mold exposure during infancy as a predictor of potential asthma development. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology, 102(2), 131–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60243-8

[24] Flournoy, R., Reddy, A., Stagg, K., Davis, V., Haggerty, R., & Grossman, D. (2021) Housing affordability and quality: A community driver of health. American Public Health Association, AcademyHealth, & Kaiser Permanente. https://www.apha.org/getcontentasset/07529a1e-bbfb-4b2e-baf2-9e9b0f3e0628/7ca0dc9d-611d-46e2-9fd3-26a4c03ddcbb/housing_health_community_driver.pdf?language=en

[25] Boch, S. J., Taylor, D. M., Danielson, M. L., Chisolm, D. J., & Kelleher, K. J. (2020). ‘Home is where the health is’: Housing quality and adult health outcomes in the Survey of Income and Program Participation. Preventive Medicine, 132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.105990

[26] Jacobs, D. E., Ahonen, E., Dixon, S. L., Dorevitch, S., Breysse, J., Smith, J., Evens, A., Dobrez, D., Isaacson, M., Murphy, C., Conroy, L., & Levavi, P. (2015). Moving into green healthy housing. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 21(4), 345‒54. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24378632/

[27] Huber, K., Nohria, R., Nandagiri, V., Whitaker, R., Tchuisseu, Y. P., Pylypiw, N., Dennison, M., Van Stekelenburg, B., Van Vleet, A., Perez, M. R., Morreale, M. C., Thoumi, A., Lyn, M., Saunders, R. S., & Bleser, W. K. (2024). Addressing housing-related social needs through Medicaid: Lessons from North Carolina’s Healthy Opportunities Pilots Program. Health Affairs, 43(2), 190–199. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2023.01044

[28] U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. (2008, June). Guide to sustaining effective asthma home intervention programs. hud_guide-to-sustaining-effective-asthma-home-intervention-programs.pdf

[29] Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2022, November 1) HHS approves Arkansas’ Medicaid waiver to provide medically necessary housing and nutrition support services. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/hhs-approves-arkansas-medicaid-waiver-provide-medically-necessary-housing-and-nutrition-support

[30] Arkansas Department of Health. (2022, October 21). National lead poisoning prevention week is October 23-29, 2022. https://healthy.arkansas.gov/article/national-lead-poisoning-prevention-week-is-october-23-29-2022/

[31] Jacobs, D. E., Tobin, M., Targos, L., Clarkson, D., Dixon, S. L., Breysse, J., Pratap, P., & Cali, S. (2016). Replacing windows reduces childhood lead exposure: Results from a state-funded program. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 22(5), 482-491. DOI: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000389

[32] National Center for Healthy Housing. (2022, April). Studying the optimal ventilation for environmental indoor air quality. https://nchh.org/resource-library/report_studying-the-optimal-ventilation-for-environmental-indoor-air-quality.pdf

[33] The Community Guide. (2018, October 1). Asthma: Home-based multi-trigger, multicomponent environmental interventions: Children and adolescents with asthma. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/asthma-home-based-multi-trigger-multicomponent-environmental-interventions-children-adolescents-asthma.html

[34] Marshall, E. T., Guo, J., Flood, E., Sandel, M. T., Sadof, M. D., & Zotter, J. M. (2020). Home visits for children with asthma reduce Medicaid costs. Preventing chronic disease, 17, E11. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd17.190288

[35] National Center for Healthy Housing. Hospital community benefits. Accessed July 22, 2025. https://nchh.org/tools-and-data/financing-and-funding/healthcare-financing/hospital-community-benefits/

[36] Leider, J. P., Tung, G. J., Lindrooth, R. C., Johnson, E. K., Hardy, R., & Castrucci, B. C. (2017). Establishing a baseline: Community benefit spending by not-for-profit hospitals prior to implementation of the Affordable Care Act. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 23(6), e1–e9. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0000000000000493

[37] United Health Foundation. Rural population in Arkansas. America’s Health Rankings. Accessed July 22, 2025. https://www.americashealthrankings.org/explore/measures/pct_rural_b/AR

[38] Oregon Revised Statutes, ORS § 442.624 (2019). https://oregon.public.law/statutes/ors_442.624

[39] National Center for Healthy Housing. (2008). Fact Sheet: Background on the importance of healthy housing for older adults. https://nchh.org/resource-library/fact-sheet_background-on-the-importance-of-healthy-housing-for-older-adults.pdf

[40] Arkansas Act 1052 of 2021. https://arkleg.state.ar.us/Home/FTPDocument?path=/ACTS/2021R/Public/ACT1052.pdf

[41] Foster, L. (2025, February 27). Landlord-tenant laws. Encyclopedia of Arkansas. https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/landlord-tenant-laws-8479/

[42] City of Little Rock. Tenant rights. https://www.littlerock.gov/city-administration/city-departments/housing-and-neighborhood/tenant-rights/

[43] National Center for Healthy Housing. (2024, May). Arkansas 2024 healthy housing fact sheet. https://nchh.org/resource-library/fact-sheet_state-healthy-housing_ar.pdf