Author

Elizabeth (Izzy) Montgomery, MPA

Health Policy Analyst

Contact

ACHI Communications

501-526-2244

jlyon@achi.net

The term “private equity” refers to an investment strategy in which investors pool large amounts of money to purchase companies, improve their value, and quickly sell the companies for a profit.[1] In recent years, private equity firms have increased their activity in the healthcare sector, purchasing hospitals, physician practices, nursing homes, and other types of healthcare entities. In 2024 alone, there were approximately 1,069 unique private equity-backed healthcare deals in the U.S.[2] However, the rapid growth of private equity in health care has raised concerns. While supporters argue that private equity investments are needed to provide capital and efficiency to struggling healthcare systems and providers, critics have raised concerns about potential impacts on quality, access, and cost.[3] In this explainer, we define private equity firms and transactions, describe the role of private equity in the healthcare system, examine national and state trends, and outline efforts to regulate private equity investment in the healthcare sector.

Table of Contents

– Background

- What Is Private Equity in Health Care?

- Increased Presence of Private Equity in Health Care

- Private Equity Acquisition Models and Financial Risk

– Impacts of Private Equity on Quality, Access, and Cost

– Private Equity Healthcare Transactions in Arkansas

Background

WHAT IS PRIVATE EQUITY IN HEALTH CARE?

Private equity in health care is a “form of for-profit ownership reflecting investment in health care facilities by private parties.”[4] Private equity firms use investor capital and borrowed funds to purchase healthcare facilities, with the goal of generating a high return on their investment by improving the facilities’ operations and increasing their value before reselling — typically within three to seven years. These acquisitions usually involve significant cost-cutting, management changes, and prioritization of revenue-generating services as key strategies to increase profitability and value. This short-term investment strategy is different from the strategies employed by venture capital firms, which typically invest earlier in a company’s lifecycle and take a longer-term approach.

INCREASED PRESENCE OF PRIVATE EQUITY IN HEALTH CARE

The healthcare sector is an attractive investment area for private equity firms for several reasons. First, it is often viewed as “recession proof,” meaning that healthcare systems are less vulnerable to the negative consequences of economic downturns than other industries because the demand for healthcare services will always exist. Many types of healthcare services also generate predictable and high-volume revenue streams, particularly in outpatient settings such as urgent care clinics, behavioral health facilities, and specialty physician practices. In addition, many aspects of the healthcare sector have historically been fragmented into many small or independently owned providers. This fragmentation presents opportunities for private equity firms to consolidate these independent practices into larger, more efficient systems to generate increased revenue.[4] Finally, regulatory gaps and limited ownership transparency have fueled the growth of private equity transactions in health care, allowing these transactions to occur with minimal oversight at the state and federal levels.

Examples of healthcare investments by private equity firms include:

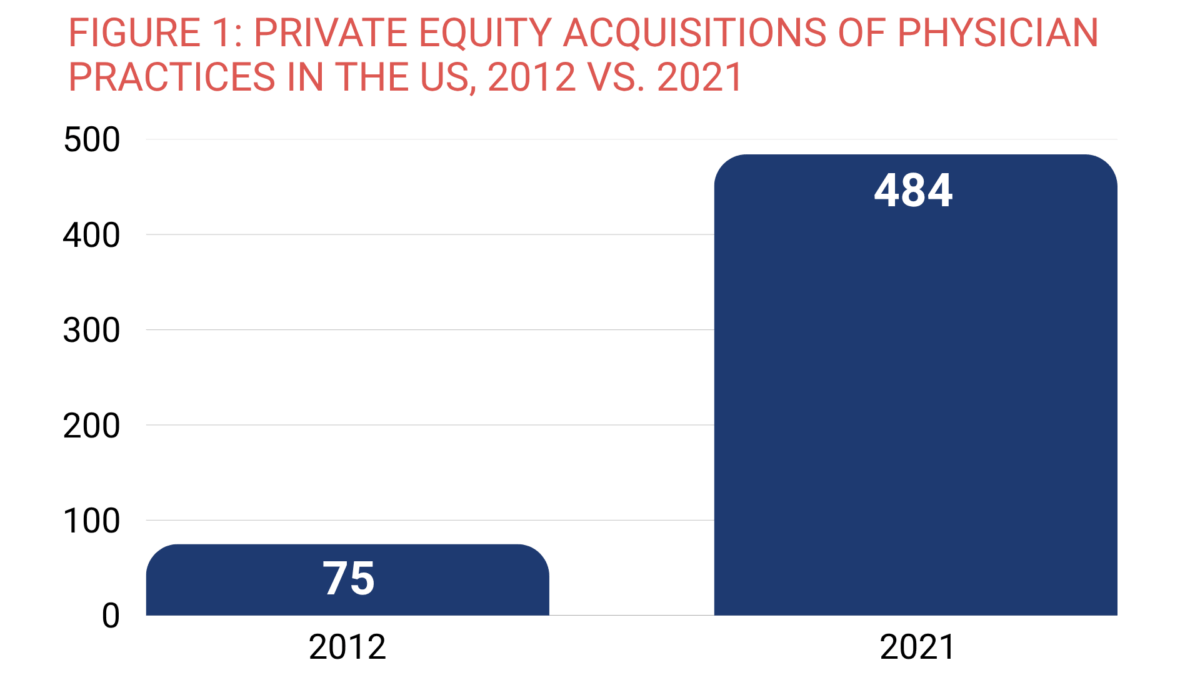

- Physician practices. Private equity firms have often targeted high-margin specialty practices such as cardiology, dermatology, and gastroenterology because they offer predictable cash flow and opportunities for consolidation. Firms have also increasingly invested in primary care practices, a move often attributed to consolidation opportunities, increased demand for coordinated care, and the potential to negotiate higher reimbursement rates from commercial payers.[5] Figure 1 shows the growth in acquisitions of physician practices between 2012 and 2021.[6]

- Nursing homes and other long-term care facilities. The demand for long-term care has grown due to an aging population in the U.S. These facilities typically provide stable revenue streams, as most residents are covered by Medicare, Medicaid, or both. Medicare will pay for skilled nursing care, but only for short-term stays following a hospital admission. In contrast, many long-term residents are covered by Medicaid or private long-term care insurance. The Government Accountability Office estimates that 5% of the 14,800 nursing homes enrolled in Medicare had private equity owners in 2022.[7]

- Behavioral health facilities. These are appealing to private equity investors due to high demand and rapid sector growth associated with increasing recognition of mental health and substance use disorder needs. Since 2018, more than 60% of private equity firm deals have involved behavioral health organizations.[8]

PRIVATE EQUITY ACQUISITION MODELS AND FINANCIAL RISK

The way private equity firms acquire healthcare entities introduces a new kind of financial risk into the healthcare system. When a private equity firm decides to purchase a healthcare entity, it typically does so through a process known as a leveraged buyout — a method which relies heavily on borrowed money to fund the investment.[9] In most cases, the private equity firm borrows a large portion of the purchase price, often using the healthcare entity’s own assets or projected future revenue as collateral. As a result, the acquired healthcare entity is left carrying the debt that was used to purchase it. Facilities acquired through leveraged buyouts are nearly 10 times more likely to go bankrupt.[10]

Along with the leveraged buyout, private equity firms also utilize growth investments and add-on acquisition models to acquire healthcare entities. Growth investments typically involve private equity firms providing capital to help established healthcare entities expand their operations, often by financing additional acquisitions or supporting other expansion efforts such as upgrading technology systems or launching new service lines. The add-on acquisition model involves expanding an existing company by acquiring smaller companies and integrating them into it — for example, expanding a large, established urgent care chain by purchasing smaller and lesser-known facilities to add to the chain.[2]

Impacts of Private Equity on Quality, Access, and Cost

Evidence is mixed regarding quality and patient health outcomes. A 2025 study found that after acquisition, private equity-owned hospitals reduced salary and staffing in their emergency departments and intensive care units.[11] This occurred alongside an increase in transfers of patients, who were on average sicker, to other hospitals and a 13.4% rise in deaths that occurred in the emergency department. A National Institutes of Health study published in 2023 showed that in hospitals acquired by private equity firms, hospital-acquired conditions among Medicare beneficiaries increased by 25% compared to rates of the same conditions in hospitals not owned by private equity firms. The same study showed that private equity acquisition was associated with a 27% increase in falls and a 38% increase in infections following central line placement.[12] A 2025 study also found that private equity acquisition was associated with a 2.7-percentage-point increase in 30-day postoperative mortality compared to non-private equity-controlled hospitals.[13] However, a 2022 study of 21 million Medicare beneficiaries found an association between private equity acquisition of hospitals and lower rates of inpatient mortality and 30-day mortality (i.e., fewer patients died within 30 days of being admitted to the hospital) among beneficiaries with acute myocardial infarction.[14] Another study looked at 204 hospitals acquired by private equity firms and found that compared to 532 control hospitals, the private equity-acquired hospitals showed improvements in process-based quality measures related to the treatment of myocardial infarction and pneumonia.[15]

Private equity ownership has also been shown to create barriers to care. Private equity-owned providers may shift their patient mix to favor commercial patients with higher reimbursement rates, creating access barriers for low-income patients with Medicaid coverage. A 2022 study showed Medicaid acceptance was lower at private equity-owned urology practices compared to practices not owned by private equity.[16]

Private equity ownership of healthcare facilities is often associated with higher costs. A 2023 systematic review of private equity ownership trends found that private equity ownership was consistently associated with cost increases for both patients and payers.[17] Other studies have found increases in the charged and allowed amount per claim following private equity acquisitions of independent physician practices.[5]

Private Equity Healthcare Transactions in Arkansas

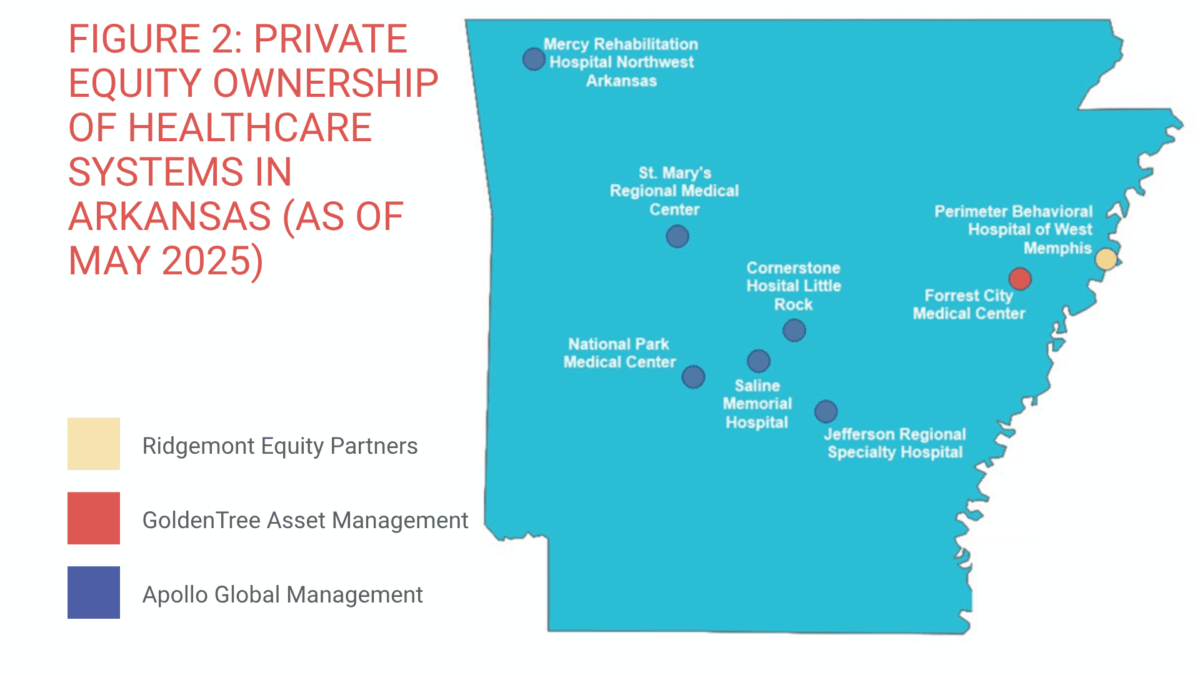

As of April 2025, at least eight hospital systems that included a total of 11 hospitals in Arkansas were controlled by private equity firms.[18] Figure 2 shows the locations of these hospitals and identifies the private equity firms that own them.[a]

At least two hospitals that serve Arkansans have been negatively impacted by private equity transactions. In 2024, Wadley Regional Medical Center, with facilities in Hope and the border town of Texarkana, Texas, risked immediate closure when their owner, Steward Health Care, declared bankruptcy. The fallout from the bankruptcy led the company to put all 31 of its hospitals up for sale to settle its $9 billion debt. However, a federal bankruptcy judge approved the sale of the two facilities to non-private equity owners, allowing the hospitals to continue operating. Pafford Medical Services, a locally based provider, agreed to purchase the Hope facility, and CHRISTUS Ark-La-Tex, a nonprofit health system, agreed to purchase the Texarkana facility.[19]

Regulation of Private Equity Transactions

Private equity transactions are difficult to regulate at the federal level, in part because private equity firms are not publicly traded and many of their deals fall below the threshold that triggers federal antitrust review. A 2022 study estimated that more than 90% of private equity transactions are exempt from federal regulatory review.[20] Additionally, private equity firms are often structured in ways that make it difficult to understand the true ownership of a healthcare facility. Private equity firms often operate through a complex structure of subsidiaries or limited liability companies, which can make it difficult for regulators to track ownership.[15]

While there have been hearings and legislative proposals at the federal level to stimulate greater transparency around private equity in healthcare, it is unclear whether meaningful federal action is likely to take place anytime soon. While antitrust enforcement actions through the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission did occur under the Biden administration, it is uncertain how federal oversight will change under the current administration.[3]

In response to limited federal oversight, some states have pursued reforms. The National Academy for State Health Policy has developed model state legislation to address issues of corporate and private equity entry into healthcare markets.[21] As of May 2025, at least 35 states require hospitals, health systems, physician groups, and/or private equity firms to notify state authorities of certain proposed transactions — such as mergers, facility closures, or contractual affiliations.[22] Fifteen of those states regulate transactions that involve both nonprofit and for-profit healthcare entities, with the remaining states only regulating nonprofit healthcare entity transactions.

Some states have moved beyond notification requirements to require more formal review and approval of certain healthcare transactions, particularly when there are concerns about significant market consolidation, reduced access to care, or the financial stability of the acquiring entity. These more stringent reviews are often triggered when a proposed transaction constitutes a “material change” (e.g., a merger, acquisition, or purchase by a private equity entity) that could significantly change the ownership, structure, or operations of a healthcare entity.

Fifteen states have legislation in place to require parties to certain transactions to provide notice and related disclosures to state regulators, also known as “mini-HSR” laws. These are state laws modeled after the federal Hart-Scott-Rodino Act, an antitrust law that requires companies to file premerger notifications with regulators. Prior to 2020, much of this legislation focused only on hospital mergers and acquisitions. More recently, many states have expanded their regulatory scope to better address issues related to antitrust concerns, with Massachusetts taking one of the most aggressive stances to date. In January 2025, the state enacted a law that would provide state regulators greater authority to review material change transactions, particularly those related to private equity transactions.[23]

Some states have also utilized enforcement of corporate practice of medicine (CPOM) laws, which prohibit corporations or non-physician companies from owning healthcare entities. While at least 33 states have such laws in place, private equity firms often circumvent them by using a legal structure known as a “management services organization,” a separate business entity that handles non-clinical operations while the ownership of the practice is still technically provider-owned. Oregon recently passed legislation that would close such a loophole by limiting how management services organizations operate within the state.[24] While Arkansas is one of the 33 states with CPOM laws in place, there have been no known enforcement actions related to private equity transactions in the state.

Conclusion

Private equity continues to grow its presence in the U.S. healthcare system. While private equity firms may provide needed capital and operational efficiencies for healthcare entities, the financial risks these relationships carry and the short-term thinking that often lies behind them may conflict with what is in the best interests of patients and their communities. The growing presence of private equity also raises serious issues around transparency and accountability. Policymakers should continue efforts to strengthen regulations, improve transparency, and expand data reporting to ensure that private equity investments support and contribute positively to the health of communities.

References

[1] Lee, S. S., Ke, J., Shahinian, V., & Dupree, J. M. (2024, November 8). Private equity in health care: A state-based policy perspective. Health Affairs. https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/forefront/private-equity-health-care-state-based-policy-perspective

[2] Bugbee, M., O’Grady, E., & Fenne, M. (2025). Private equity healthcare deals: 2024 in review. Private Equity Stakeholder Project. https://pestakeholder.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/PESP_Report_HC-Acquisitions_2025.pdf

[3] Blumenthal, D. (2023, November 17). Private equity’s role in health care. The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/explainer/2023/nov/private-equity-role-health-care

[4] Zhu, J. M., & Song, Z. The growth of private equity in US health care: Impact and outlook. NIHCM Foundation. Accessed May 18, 2025. https://nihcm.org/publications/the-growth-of-private-equity-in-us-health-care-impact-and-outlook

[5] Singh, Y., Radhakrishnan, N., Adler, L. (2025). Growth of private equity and hospital consolidation in primary care and price implications. JAMA Health Forum, 6(1), e244935. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2024.4935

[6] Scheffler, R.M., Alexander, L., Fulton, B.D., Arnold, D.R., and Abelhadi, O.A. Monetizing Medicine: Private Equity and Competition in Physician Practice Markets. American Antitrust Institute, the Nicholas C. Petris Center on Health Care Markets and Consumer Welfare, University of California, Berkeley, and the Washington Center for Equitable Growth. https://www.antitrustinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/AAI-UCB-EG_Private-Equity-I-Physician-Practice-Report_FINAL.pdf

[7] U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2023, September 22). Nursing homes: Limitations of using CMS data to identify private equity and other ownership. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-23-106163

[8] The BRAFF Group. Behavioral health mergers & acquisitions: Year in Review: 2023. Accessed May 15, 2025. https://thebraffgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/BH-Year-End-Report-2023.pdf

[9] Offodile, A. C., II, Cerullo, M., Bindal, M., Rauh-Hain, J. A., & Ho, V. (2021). Private equity investments in health care: An overview of hospital and health system leveraged buyouts, 2003-17. Health Affairs, 40(5), 719–726. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01535

[10] Comondore, V. R., Devereaux, P. J., Zhou, Q., Stone, S. B., Busse, J. W., Ravindran, N. C., Burns, K. E., Haines, T., Stringer, B., Cook, D. J., Walter, S. D., Sullivan, T., Berwanger, O., Bhandari, M., Banglawala, S., Lavis, J. N., Petrisor, B., Schünemann, H., Walsh, K., Bhatnagar, N., … Guyatt, G. H. (2009). Quality of care in for-profit and not-for-profit nursing homes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ, 339, b2732. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2732

[11] Kannan, S., Bruch, J. D., Zubizarreta, J. R., Stevens, J., & Song, Z. (2025) Hospital staffing and patient outcomes after private equity acquisition. Annals of Internal Medicine. doi:10.7326/ANNALS-24-03471

[12] Kannan, S., Bruch, J. D., & Song, Z. (2023). Changes in hospital adverse events and patient outcomes associated with private equity acquisition. JAMA, 330(24), 2365–2375. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2023.23147

[13] Diaz, A., Mead, M., Rohde, S., Kunnath, N., Dimick, J. B., & Ibrahim, A. M. (2025). Hospitals acquired by private equity firms: Increased postoperative mortality for common inpatient surgeries. Health Affairs, 44(5), 554–562. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2024.01102

[14] Cerullo, M., Lin, Y. L., Rauh-Hain, J. A., Ho, V., & Offodile, A. C., 2nd (2022). Financial impacts and operational implications of private equity acquisition of US hospitals. Health Affairs, 41(4), 523–530. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01284

[15] Bruch, J. D., Gondi, S., & Song, Z. (2020). Changes in hospital income, use, and quality associated with private equity acquisition. JAMA Internal Medicine, 180(11), 1428–1435. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3552

[16] Massachusetts Health Policy Commission. (2024). HPC policy brief: Private equity investments in Massachusetts health care and state policy options. https://masshpc.gov/sites/default/files/2024_Private_Equity_Investments.pdf

[17] Borsa, A., Bejarano, G., Ellen, M., & Bruch, J. D. (2023). Evaluating trends in private equity ownership and impacts on health outcomes, costs, and quality: Systematic review. BMJ, 382, e075244. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2023-075244

[18] Private Equity Stakeholder Project. (2025, April). PESP Private Equity Hospital Tracker. https://pestakeholder.org/private-equity-hospital-tracker/

[19] Wilson, C. (2024, October 3). A cautionary tale about private equity and healthcare. Talk Business & Politics. https://talkbusiness.net/2024/10/a-cautionary-tale-about-private-equity-and-healthcare/

[20] Zhu, J. M., & Song, Z. The growth of private equity in US health care: Impact and outlook. NIHCM Foundation. Accessed May 18, 2025. https://nihcm.org/publications/the-growth-of-private-equity-in-us-health-care-impact-and-outlook

[21] National Academy for State Health Policy. (2024, July 26). Comprehensive consolidation model addressing transaction oversight, corporate practice of medicine and transparency. https://nashp.org/a-model-act-for-state-oversight-of-proposed-health-care-mergers/

[22] Jaromin, S. (2024, August 19). The evolving landscape of state health care transaction laws. National Conference of State Legislatures. https://www.ncsl.org/health/the-evolving-landscape-of-state-health-care-transaction-laws

[23] Goheen, J., Harrington, J., and Jensen, A. (2025, March 20). States continue to pursue and expand healthcare market oversight at an unprecedented pace, with significant implications for private equity. Goodwin. https://www.goodwinlaw.com/en/insights/publications/2025/03/alerts-privateequity-hltc-states-continue-to-pursue-and-expand?utm_source=alrts&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=PRA&utm_term=HLTC&utm_content=20250320_alrt_hltc_antc_States%20Continue%20to%20Pursue%20and%20Expand%20Healthcare#msdynmkt_trackingcontext=8480905b-35ab-425f-a367-e4f45cb40300

[24] VanderHart, D. (2025, May 28). Oregon lawmakers vote to block rising corporate ownership of medical clinics. OPB. https://www.opb.org/article/2025/05/28/oregon-lawmakers-sb-951-health-care-corporate-medical-clinics/

[a] Since there is no required reporting in Arkansas, it is unknown how many more hospitals or other healthcare entities are private equity-owned.