While the budget reconciliation law signed on July 4, 2025, broadly reduces federal spending on health care, one area receives a multibillion-dollar expansion: health savings accounts (HSAs). This explainer examines how HSAs work, their advantages and disadvantages, and how their eligibility rules will change under the 2025 budget law.

Table of Contents

Background

HSAs are tax-advantaged accounts that can be used to pay for certain healthcare expenses, such as copays, coinsurance, and prescription medications.1 HSA holders, and often their employers, can make contributions to HSAs up to an annual limit set by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). For 2025, the limit is $4,300 for individuals and $8,550 for families.2 HSAs may only be held by beneficiaries of high-deductible health plans (HDHPs) designated as HSA-eligible by the IRS.3

High-Deductible Health Plan (HDHP)

An HDHP is a health insurance plan that offers a low monthly premium in exchange for a high annual deductible.

HDHPs are favored by young, healthy people who have minimal routine healthcare spending and desire catastrophic coverage at minimal monthly cost.

HSAs are often called “triple tax-advantaged,”4 because they offer three distinct opportunities for tax savings:2

- Individual contributions to an HSA are tax-deductible, and contributions made by an employer or through employer withholding are made on a pre-tax basis.

- Any returns on the investment of funds in an HSA are tax-free.

- Withdrawals from an HSA are tax-free, if used for certain qualifying expenses.

HSAs are often confused with two similar alternatives:

- Flexible spending accounts (FSAs): FSAs are open to people with employer-sponsored insurance that is not HSA-eligible. As with an HSA, an employee contributes to an FSA through a pre-tax withholding, and qualifying withdrawals are tax-free.

- Health reimbursement arrangements (HRAs): Unlike HSAs and FSAs, an employee does not contribute to an HRA, and the employer has total control over the funds. Like HSAs, HRAs can be held concurrently with an HDHP.

TABLE 1: A COMPARISON OF TAX-ADVANTAGED* ACCOUNTS FOR HEALTHCARE EXPENSES2,5,6

| Health Savings Account | Health Reimbursement Arrangement | Flexible Spending Account | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tax Benefit | Triple-tax-advantaged: no tax on contributions, interest, or qualifying withdrawals. | Contributions are only made by the employer, and employer contributions are not reported as income. | Employee contributions are made pre-tax, reimbursement for qualifying expenses is tax-free, and employer contributions are not reported as income. |

| Portability | Owned by the beneficiary; remains after employment. | Owned by the employer; funds lost if employment ends. | Owned by the employer; funds lost if employment ends. |

| Annual Rollover | All funds roll over year-over-year and serve as a long-term investment in health. | Varies at employer’s discretion; may allow full, partial, or no rollover. | Some rollover allowed up to a max set by the IRS ($660 in 2025). Some employers offer a 2 1/2-month grace period to spend last year’s funds. |

| Investment | May be invested once a balance threshold is met; interest is tax-free. | Not invested, except for some retiree HRAs. | Not invested. |

| Contribution Limit | Set annually by the IRS ($4,300 individual, $8,550 family in 2025). | Set by the employer; however, six special HRA types have IRS-defined limits (some have no limit). | Set annually by the IRS ($3,300, with no scaling for family size, in 2025). |

| Withdrawals | Cash withdrawals for non-health spending are allowed, but with a 20% penalty tax in addition to income taxes. | Employers decide what expenses qualify; employees pay out of pocket and are reimbursed. No cash withdrawals. | Qualifying expenses can be paid directly from the account or reimbursed, but cash withdrawals are prohibited. |

*References to “tax-free” or “no tax” mean no federal income tax and no employment taxes (i.e., Medicare and Social Security) are collected. Some states may still apply state income tax. Sales taxes may apply at the point of purchase but are generally eligible for reimbursement.

HSAs were introduced with the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 20037 as a means of curbing rapidly growing healthcare spending and overutilization of covered services, encouraging personal financial responsibility in health, and shifting more control — and with it more risk — to individual consumers.

Unlike traditional health insurance plans, in which beneficiaries pay a share of the total costs charged by providers through copays or coinsurance, enrollees in HDHPs generally pay the full costs of services out of pocket until meeting their deductible. Proponents of HDHPs argue that this structure empowers consumers to freely select providers according to their own appraisal of cost and quality of care, which puts market pressure on providers to offer lower base prices.8 While most traditional health insurance plans limit coverage to a network of preferred providers or offer reduced benefits for out-of-network care, HDHPs with HSAs have no such restriction; expenses can be paid from an HSA on a tax-advantaged basis to any provider, giving beneficiaries more flexibility in how they seek care. Proponents of HSAs say that, by providing a strongly subsidized avenue for long-term savings and investment, HSAs prepare young beneficiaries for greater healthcare spending later in life.

“Traditional” Insurance Models

Insurers offer a variety of other insurance models besides HDHPs. Compared to HDHPs, these models are more “traditional” in that they cover part of the cost of beneficiaries’ health care without requiring them to meet a deductible, with restrictions depending on the specific model. Some common models are:

Preferred Provider Organization (PPO)

Covers care from in-network providers and gives partial coverage for care from out-of-network providers.

Point-of-Service Plan (POS)

Similar to a PPO, but typically requires referrals for specialist care, even in-network.

Exclusive Provider Organization (EPO)

Only pays for services from in-network providers, except in emergencies.

Health Maintenance Organization (HMO)

Similar to an EPO, but typically with added location restrictions and a focus on primary, preventive care.

Critics of HSAs contend that the accounts disproportionately benefit higher-income people while driving low-income consumers into weaker health plans.9 Higher-income households on average make larger contributions, claim larger tax deductions per beneficiary, and save more on their taxes per dollar contributed. Critics also say that, while HDHPs with HSAs are modestly successful at reducing healthcare spending and discouraging overutilization,10 they also reduce consumption of health care overall, including necessary preventive and specialty care.11

TABLE 2: COMPARISON OF EMPLOYER-SPONSORED INSURANCE MODELS IN ARKANSAS, 202414

| HDHPs | PPOs | |

|---|---|---|

| Share of Workers Covered | 38.8% | 56.3% |

| Average Monthly Premium, Single | $461 | $518 |

| Median Annual Deductible | $3,000 | $1,500 |

| Median Out-of-Pocket Maximum | $3,750 | $5,000 |

For better or worse, HDHPs make up a significant portion of health insurance nationwide. In 2023:12

- 41.7% of Americans under age 65 with private insurance were enrolled in HDHPs, down from 2021’s enrollment peak of 43.3%.

- 19.5% of Americans under age 65 with private insurance were enrolled in an HDHP with an HSA, and 27.3% were enrolled in an HDHP with no HSA.

- Likely because of the availability of HSAs, HDHPs are more popular among people with higher incomes: 24.1% of privately insured people with incomes below 139% of the federal poverty level were enrolled in an HDHP, compared to 45.3% of people with incomes above 400% of the federal poverty level.

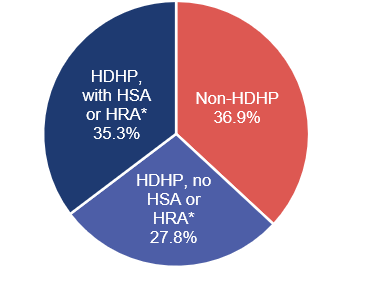

FIGURE 1: ENROLLMENT IN INDIVIDUAL HEALTH PLANS AMONG PRIVATE-SECTOR WORKERS IN ARKANSAS, 202415

*Plans are counted as having an HSA or HRA in this chart only if there was evidence of an employer contribution. While rare, some employers do not make contributions to their employees’ HSAs.

HDHPs with an attached HSA are especially popular as employee-sponsored plans. Employers get to shift risk to employees and thereby spend less on cost sharing and premiums, and employees typically get contributions to their accounts from their employers (usually $650 annually in Arkansas), in addition to their own pre-tax contributions.

More nationwide statistics:12,13

- Between 2019 and 2023, people who acquired health insurance through their employer were four times more likely to be enrolled in an HDHP with an HSA compared to those buying individual plans.

- In 2023, 21.7% of Americans under age 65 with employer-sponsored coverage enrolled in an HDHP with an HSA, compared to 5.6% of people under 65 who purchased their insurance directly from an insurance company.

- Overall enrollment in HDHPs is comparable between those with employment-based coverage and those with directly purchased coverage.

- Access to HSA-eligible plans has increased every year in the last decade among those with employer-sponsored coverage, from 24% of workers having at least one HSA-eligible option in 2015 to 39% of workers in 2024.

2025 Budget Reconciliation Changes to HSA Eligibility

The original version of the 2025 budget reconciliation bill passed by the U.S. House made sweeping expansions to eligibility for HSAs, amounting to nearly $45 billion in additional federal spending.16 While most of these provisions were removed in the Senate’s version — which ultimately became law — three key provisions were retained.17 Collectively, these provisions represent an estimated $10.69 billion in additional federal spending over the next 10 years.18

ACA CATASTROPHIC AND BRONZE PLANS NOW HSA-ELIGIBLE

Previously, bronze-tier plans offered on the Affordable Care Act (ACA) health insurance marketplace — which usually have the lowest monthly premiums but the highest costs when you get care — were not necessarily HSA-eligible, and catastrophic plans were categorically HSA-ineligible. The new law classifies all individual bronze and catastrophic plans offered on the ACA health insurance marketplace as HSA-eligible HDHPs. This means that the enrollee will be able to hold and make contributions to an HSA, even if the plan would not meet the IRS requirements for HSA-eligibility were it not on the marketplace.

Nationwide in 2024, there were 1,693 bronze plans offered through Healthcare.gov, of which 267 were HSA-eligible, covering 9.3% of bronze plan enrollees.19,20 In addition, there were 163 catastrophic plans available.20 Arkansas had 14 bronze plans available, of which only one was HSA-eligible, covering 2% of bronze plan enrollees. There were no catastrophic plans available on the Arkansas Health Insurance Marketplace in 2024. The ACA premium tax credit cannot be applied to catastrophic plans, so insurers replaced these with tax-credit-eligible bronze plans in most states following passage of the American Rescue Plan Act in 2021, which temporarily enhanced the value of premium tax credits.20,21

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that this provision will cost the federal government $3.56 billion over 10 years.18

TABLE 3: ACA MARKETPLACE ENROLLMENT* IN BRONZE AND CATASTROPHIC PLANS, 2024 (AR VS. US)19,20

Percentage of Enrollees in Bronze Plans (Number of People) | Percentage of Enrollees in Catastrophic Plans (Number of People) |

|

|---|---|---|

| U.S. | 30% (4,682,336) | 0.1% (15,742) |

| Arkansas | 24% (32,017) | 0% |

*Data include only the 32 states that used Healthcare.gov to administer their ACA marketplaces in 2024. These figures are a sum of the average number of enrollees across 12 months for each available individual plan. Off-marketplace plans and supplemental plans (dental- and vision-only plans) are excluded.

SOME DIRECT PRIMARY CARE ARRANGEMENTS NO LONGER CONSIDERED HEALTH PLANS

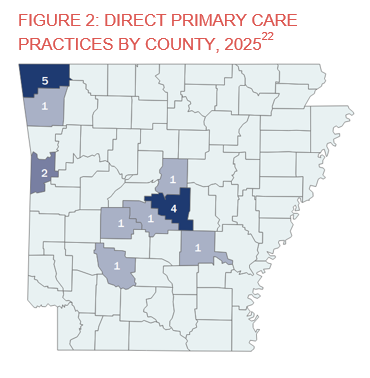

Direct primary care (DPC) is a growing practice and payment model in which a patient pays a monthly membership fee to access all services from a primary care practitioner, rather than paying a fee for each visit or service rendered. Arkansas currently has 17 DPC practices (physician’s offices using this model) across the state, and there are 2,611 DPC practices nationwide.22 Arkansas is also home to one on-site employee clinic that operates under the same model. In 2024, the average DPC practice in the U.S. had 413 members, with monthly individual membership fees ranging from $50 to $100.23

The federal government broadly considers DPC arrangements to be a form of health insurance plan, and an HSA holder is prohibited by law from holding another health insurance plan.24 Under the 2025 budget law, however, certain DPC arrangements will no longer be classified as health insurance plans. The House version of the budget bill also included on-site employee clinics in this change, but this was removed in the Senate version.17

DPC arrangements are only eligible for this reclassification if they are limited to primary care services provided by primary care practitioners. Any DPC arrangement that offers general anesthesia, prescription drugs (excluding vaccines), or atypical laboratory services will still be considered a health insurance plan.

The new law also allows DPC membership fees to be paid out of an HSA. This provision does not apply if an individual’s monthly membership fee exceeds $150. If a person has multiple DPC arrangements, the total monthly cost across all arrangements still cannot exceed $150. This monthly cap is raised to $300 if any one DPC arrangement covers more than one individual, but this cap is not scaled based on the number of individuals; a family of two and a family of 10 both have the same $300 monthly cap.

In summary, starting Jan 1, 2026:

- Beneficiaries of HSA-eligible HDHPs will be able to join a DPC arrangement without losing their HSA.

- Current members of a DPC arrangement will be able to enroll in any bronze-tier marketplace plan and open an HSA, regardless of whether that plan is HSA-eligible under IRS rules.

- Monthly fees for DPC arrangements will be able to be paid out of HSAs on a heavily tax-advantaged basis.

The CBO estimates that this provision will cost the federal government $2.81 billion over 10 years.18

PERMANENT EXTENSION OF RULE ALLOWING HSA-ELIGIBLE HDHPS TO COVER TELEHEALTH SERVICES BEFORE DEDUCTIBLE IS MET

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act of 2020 temporarily allowed HDHPs to cover telehealth services before a deductible was met and retain their HSA-eligible status.25 The law also made holding separate coverage for telehealth and other remote services concurrently with an HDHP no longer a disqualification from making HSA contributions.

These relaxed rules were in effect from 2021 through 2024, but they expired on January 1, 2025. The new law makes reinstates these changes and makes them permanent, once again allowing HDHP beneficiaries much greater access to telehealth services. This provision’s effective date is December 31, 2024, allowing employers and their insurers to offer pre-deductible coverage for telehealth retroactively to that date. The legislation does not mandate pre-deductible coverage, however, so insurance plans may not necessarily offer retroactive reimbursements or include this coverage in future plan years. Beneficiaries of HDHPs must contact their health plan and/or employer to determine if this coverage will be available. The CBO estimates that this provision will cost the federal government $4.32 billion over 10 years.18

Conclusion

The 2025 budget law expands access to HSAs for marketplace enrollees, allows HSA holders to participate in the DPC model, and improves access to telehealth for people with HDHPs. Collectively, these three provisions are estimated to increase federal spending by $10.69 billion over 10 years. With looming federal changes to ACA subsidies expected to increase monthly premiums for many marketplace plans, many Americans will turn to HDHPs for affordable coverage. Proponents say these changes are a timely improvement to an insurance model that gives consumers greater control over their care. Critics complain that expansion of HSAs will provide limited practical benefit to enrollees with lower incomes, may not sufficiently offset the impact of subsidy reductions, and may disproportionately benefit high-income enrollees. Regardless, beginning in 2026, most HDHP enrollees will see greater flexibility and/or additional benefits.

References

1 Choi A, Rosso R. Health savings accounts (HSAs). Congress.gov. February 11, 2025. Accessed September 2, 2025. https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R45277

2 Internal Revenue Service. Publication 969 (2024), health savings accounts and other tax-favored health plans. IRS.gov. Accessed September 2, 2025. https://www.irs.gov/publications/p969

3 Internal Revenue Service. Internal Revenue Bulletin: 2025-21. IRS.gov. May 19, 2025. Accessed September 2, 2025. https://www.irs.gov/irb/2025-21_IRB

4 HSA triple tax advantages explained. Fidelity. March 3, 2025. Accessed September 2, 2025. https://www.fidelity.com/learning-center/smart-money/are-hsa-contributions-tax-deductible

5 6 types of HRAs you should know. Benafica. March 6, 2024. Accessed August 28, 2025. https://benafica.com/6-types-of-hras-you-should-know-about/

6 HRA vs. HSA: Comparing health accounts. Fidelity. November 19, 2024. Accessed August 27, 2025. https://www.fidelity.com/learning-center/smart-money/hra-vs-hsa

7 Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act. 42 USC § 1301 (2003). December 8, 2003. Accessed July 23, 2025. https://www.congress.gov/108/plaws/publ173/PLAW-108publ173.pdf

8 HSA’s for all. HSAs for All. Accessed September 2, 2025. https://hsasforall.org/about-hsas/

9 Ross J, Ducas A. Recent health savings account (HSA) expansion proposals are costly and misguided. Center for American Progress. December 13, 2023. Accessed September 2, 2025. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/recent-health-savings-account-hsa-expansion-proposals-are-costly-and-misguided/

10 Lo Sasso AT, Shah M, Frogner BK. Health savings accounts and health care spending. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(4):1041-1060. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01124.x

11 Agarwal R, Mazurenko O, Menachemi N. High-deductible health plans reduce health care cost and utilization, including use of needed preventive services. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(10):1762-1768. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0610

12 Cohen RA, Briones EM. Enrollment in high-deductible health plans among people younger than age 65 with private health insurance: United States, 2019-2023. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2024;(214):CS354963. doi:10.15620/cdc/165797

13 High deductible health plans and health savings accounts. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. April 11, 2025. Accessed July 18, 2025. https://www.bls.gov/ebs/factsheets/high-deductible-health-plans-and-health-savings-accounts.htm

14 2024 UBA Employee Benefits Benchmarking: Trends Report. United Benefits Advisors. Accessed July 22, 2025. https://bimgroup.us/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/2024-uba-employee-benefits-benchmarking-trends-report.pdf

15 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Accessed August 27, 2025. https://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_stats/state_tables.jsp?regionid=3&year=2024.0

16 Salaga M, Pestaina K. Expansions to health savings accounts in House budget reconciliation: Unpacking the provisions and costs to taxpayers. KFF. May 29, 2025. Accessed September 2, 2025. https://www.kff.org/policy-watch/expansions-to-health-savings-accounts-in-house-budget-reconciliation-unpacking-the-provisions-and-costs-to-taxpayers/

17 Tracking the health savings accounts provisions in the 2025 reconciliation bill. KFF. July 8, 2025. Accessed September 2, 2025. https://www.kff.org/tracking-the-health-savings-accounts-provisions-in-the-2025-budget-bill/

18 Information concerning the budgetary effects of H.R. 1, as passed by the Senate on July 1, 2025. Congressional Budget Office. July 1, 2025. Accessed September 2, 2025. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/61537

19 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Issuer level enrollment data. CMS.gov. July 24, 2025. Accessed August 26, 2025. https://www.cms.gov/marketplace/resources/data/issuer-level-enrollment-data

20 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Health insurance exchange public use files (exchange PUFs). CMS.gov. August 12, 2025. Accessed September 2, 2025. https://www.cms.gov/marketplace/resources/data/public-use-files

21 American Rescue Plan Act. 15 USC § 9001 (2021). March 11, 2021. Accessed September 2, 2025. https://www.congress.gov/117/plaws/publ2/PLAW-117publ2.pdf

22 DPC Frontier Mapper. DPC Frontier. Accessed September 2, 2025. https://mapper.dpcfrontier.com/

23 Direct primary care. American Academy of Family Physicians. Accessed September 2, 2025. https://www.aafp.org/family-physician/practice-and-career/delivery-payment-models/direct-primary-care.html

24 Internal Revenue Service. Certain medical care arrangements. Federal Register. June 10, 2020. Accessed September 2, 2025. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/06/10/2020-12213/certain-medical-care-arrangements

25 Moss K, Wexler A, Dawson L, et al. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act: Summary of key health provisions. KFF. April 9, 2020. Accessed September 2, 2025. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/the-coronavirus-aid-relief-and-economic-security-act-summary-of-key-health-provisions/